- The Liner Shipping Industry

and

Carbon Emissions Policy-

- September

2009-

- The Liner Shipping Industry and Carbon Emissions Policy

-

- Dear Reader: Governments, industries, and consumers around the

world are responding to concerns about the effect of carbon dioxide

(CO2 ) emissions on climate change by determining how to design more

efficient energy and environmental practices and regulatory regimes.

We have prepared this paper to inform you about the work of the

liner shipping industry on this issue.

-

- Maritime shipping produces an estimated 2.7% of the world's CO2

emissions, while at the same time it provides an essential service

to all nations' economies and consumers. The World Shipping Council

and its Member liner shipping companies are supporting the efforts

of governments at the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to

develop a new regulatory regime addressing CO2 emissions from ships.

This work on carbon emissions follows last year's successful IMO

agreement on new regulations to reduce ships' NOx, SOx, and

particulate matter (PM) emissions. CO2 emissions are now the focus

of debate at the IMO, at the United Nations Framework Convention on

Climate Change (UNFCCC), and within the capitals of numerous

governments.

-

- In this paper you will read about many of the issues, important

principles, and challenges in constructing an effective and

efficient international carbon emission regime for shipping.

Developing that regime is difficult. It is not difficult because the

industry opposes it. It is difficult for a variety of reasons,

including: political differences between governments on how the

resulting economic burdens should be allocated; the fact that the

vast majority of ships' emissions occur outside the territory of any

government; the absence of effective precedent no transportation

mode has a comprehensive carbon emission regime that can simply be

borrowed and applied; and it is difficult because there are very

different approaches under discussion with additional proposals

likely to emerge.

-

- The task is also complicated by the fact that maritime shipping

is by far the most carbon efficient mode of transporting goods.

Despite the very significant efficiencies of marine transportation

today, further improvements in efficiency are being regularly made,

and even greater improvements will be possible in the future.

Consequently, a central challenge lies in developing a regime that

not only stimulates even greater improvements in the energy

efficiency of the world's fleet, but a regime that does not produce

an unintended consequence of shifting the transportation of goods to

other transport modes (and their consequent increase in emissions)

or otherwise discouraging maritime transportation. In fact, total

global CO2 emissions would be reduced if more goods were transported

by maritime commerce instead of the other less energy efficient

transportation modes.

-

- This paper has been organized into three sections. Part I

provides a brief description of the liner shipping portion of the

maritime shipping industry. Part II addresses common questions about

the generation of CO2 emissions from ships. Part III describes the

international process for developing new ship emission regulations,

the current status of the international discussions, and some of the

main issues that make these negotiations challenging.

-

- The liner shipping industry is committed to working with

governments and other interested organizations to develop a sound

carbon emissions regulatory regime for shipping. We hope this paper

will inform interested readers about some of the issues that we will

need to address on the road to accomplishing that objective. Please

contact us if you have any questions regarding its content.

-

- Thank you for your interest.

-

- Sincerely,

Christopher L. Koch

President and CEO-

- I. The Liner Shipping Industry

-

- What is liner shipping?

-

- Liner shipping is the service of transporting goods by means of

high capacity, ocean going ships that transit regular routes on

fixed schedules. Liner vessels, primarily in the form of container

ships and roll on/roll off ships, carry more than 581

percent of the goods by value moved internationally by sea each

year. The 29 liner shipping companies represented by the World

Shipping Council (WSC) carry approximately 90 percent of the world's

containerized ocean traffic. WSC members also serve as the principal

ocean transporters of cars, trucks and other heavy equipment around

the world.2

-

- In addition to the liner shipping sector that moves mostly

containerized goods and vehicles, the maritime industry at large

encompasses a wider set of ship operations, including tankers for

transporting liquids, bulk carriers that haul commodities such as

grain, coal and iron ore, passenger ships, cruise ships, tugs and

barges, ferries, fishing fleets, and offshore drilling and supply

vessels.

-

- The world's seaborne cargo shipping fleet consists of more than

75,000 ships3 that fly the flags of many nations and

operate regularly between ports in over 200 countries.4

-

- What is the role of the World Shipping Council?

-

- The World Shipping Council's mission is to provide a coordinated

voice for the international liner shipping industry in its work with

policymakers and industry groups on international transportation

issues. WSC works with a broad range of public and private sector

stakeholders in support of policies and programs to advance the

development of an efficient, secure, and sustainable global

transportation network. The WSC and its member companies partner

with governments and collaborate with a wide range of government and

non government organizations to formulate solutions to some of the

world's most challenging transportation problems. In 2009, the World

Shipping Council was granted consultative status at the United

Nation's International Maritime Organization (IMO), which allows WSC

to participate in the process of setting new international

regulations that will affect the liner shipping industry.

-

- Why is the liner shipping industry so important economically?

-

- It is the conduit of world trade.

Ocean shipping is

the primary conduit of world trade, a key element of international

economic development, and a central reason why the world enjoys

ready access to a diverse spectrum of low cost products. Seventy

five percent of internationally traded goods are transported via

ocean going vessels.5 In 2008, world container ship

traffic carried an estimated 1.3 billion metric tons of cargo.6

Products shipped via container include a broad spectrum of consumer

goods ranging from clothing and shoes to electronics and furniture,

as well as perishable goods like produce and seafood. Containers

also bring materials like plastic, paper and machinery to

manufacturing facilities around the world.

- It is the most efficient mode of transport for goods.

In

one year, a single large containership could carry over 200,000

containers. While vessels vary in size and carrying capacity, many

liner ships can transport up to 8,000 containers7 of

finished goods and products. Some ships are capable of carrying as

many as 14,000 TEUs (twenty foot equivalent units). It would require

hundreds of freight aircraft, many miles of rail cars, and fleets of

trucks to carry the goods that can fit on one large container ship.

In fact, if all the containers from an 11,000 TEU ship were loaded

onto a train, it would need to be 44 miles or 77 kilometers long.

- It is comparatively low cost.

Ocean shipping's

economies of scale, the mode's comparatively low cost, and its

environmental efficiencies enable long distance trade that would not

be feasible with costlier, less efficient means of transport. For

example, the cost to transport a 20 foot container of medical

equipment between Melbourne, Australia and Long Beach, California

via container ship is approximately $2,700. The cost to move the

same shipment using airfreight is more than $20,000.

- It is a global economic engine.

As a major global

enterprise, the international shipping industry directly employs

hundreds of thousands of people and plays a crucial role in

stimulating job creation and increasing gross domestic product in

countries throughout the world. Moreover, as the lifeblood of global

economic vitality, ocean shipping contributes significantly to

international stability and security.

|

5 |

Lloyd's

Maritime Intelligence Unit. See :

http://www.imsf.info/papers/NewOrleans2009/Wally_Mandryk_LMIU_IMSF09.pdf |

|

6 |

Clarkson's Research - World Seaborne

Trade - March 2009 |

|

7 |

Containers are intermodal boxes built to

international standards and specifications. The same container can

be moved by truck, on rail and via ship. The most common sizes are

20-foot containers, which are 20 feet in length and 40-foot

containers, which are 40 feet in length. The standard unit measure

for all containers is in Twenty-Foot Equivalents (TEU). A 40-foot

container equals two TEUs. |

- Why is the shipping industry so important environmentally?

-

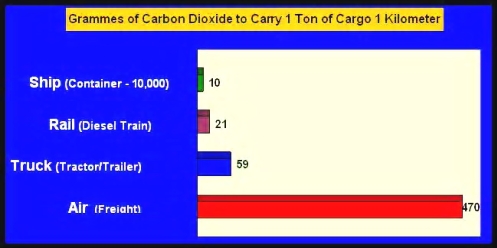

- It is the most carbon efficient mode of transportation.

As

illustrated by the graph below, ocean shipping is by far the most

carbon efficient mode of transportation. Because of its inherent

advantages, including much greater payloads per trip than ground or

air, the industry emits far less carbon dioxide (CO2 ) per ton/mile

of cargo than any other transportation mode.-

- Source: Data provided by Network for

Transport and the Environment

-

- According to the figures in this graph, transporting the 2008

volume of 1.3 billion metric tons of cargo via containership

generated approximately 13 billion grams of CO2 per kilometer . If

that same volume had been transported by airfreight instead, carbon

dioxide emissions would have increased by 4,700% to some 611 billion

grams of CO2 per kilometer.

-

- II. Carbon Dioxide Emissions (CO2 )

from Ships

-

- Ships, like all other mobile sources such as cars, trucks,

trains, and planes that are powered by fossil fuels, emit carbon

dioxide in their engine exhaust.

-

- How much carbon dioxide does the international shipping

industry emit per year?

-

- International maritime shipping accounts for approximately 2.7

percent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions.8

Container ships account for approximately 25% of that amount, while

moving roughly 52%9 of maritime commerce by value.

-

- Does international maritime shipping of goods produce more

CO2 emissions than transporting locally produced goods because of

the long transportation distances involved?

-

- Generally, the answer is no. Because maritime shipping is the

most carbon efficient form of transportation, shipping goods across

the ocean often results in fewer carbon emissions than transporting

such goods domestically.

-

- For example, a ton of goods can be shipped from the Port of

Melbourne in Australia to the Port of Long Beach in California, a

distance of 12,770 kilometers (7,935 miles), while generating fewer

CO2 emissions than are generated when transporting the same cargo in

the U.S. by truck from Dallas to Long Beach, a distance of 2,307

kilometers (1,442 miles). Similarly, a ton of goods can be moved

from the port of Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam to Tianjin, China, a

distance of 3,327 kilometers (2,067 miles) generating fewer CO2

emissions than would be generated if the same goods were trucked

from Wuhan in Central China to Tianjin, a distance of 988 kilometers

(614 miles.)10 The wine industry recently examined this

issue and found that a bottle of French wine served in a New York

restaurant will have a lower carbon transportation footprint than a

bottle of California wine served in that restaurant.11 A

whitepaper released for the Transport Intelligence Europe Conference

states that researchers evaluating this issue for the World Economic

Forum “found that the entire container voyage from China to

Europe is equaled in CO2 emissions by about 200 kilometers of long

haul trucking in Europe. So, for most freight, which is slow moving,

there is not really a green benefit to moving production to

Europe.”12

-

- In fact, shipping goods by sea to ports adjacent to major retail

markets is the most carbon efficient means of moving most products

to market in a global economy.

-

- What efforts are being made by the industry to reduce its

carbon footprint?

-

- The liner shipping industry continues its significant efforts to

reduce its carbon emissions, through a wide variety of measures.

-

- Increasing Efficiency

A recent study by Lloyd's

Register found that the fuel efficiency of container ships (4500 TEU

capacity) has improved 35% between 1985 and 2008.13 If

one compares today's largest ships with container vessels of the

1970s, the results are even more pronounced. A 1500 TEU container

ship built in 1976 consumed 178 grams of fuel per TEU per mile (or

96 grams per TEU per kilometer) at a speed of 25 knots.

The

fuel consumption per TEU per mile for a modern 12,000 TEU vessel,

built in 2007, is only 44 grams (or 24 grams per TEU per kilometer).

Looking at this example, carbon efficiency on a per mile per cargo

volume basis has improved 75% in 30 years as a result of

technological improvements and the utilization of larger vessels.

This improvement is even greater if one considers that today's ships

are operating at slower speeds that produce even greater reductions

in fuel consumption.

- Advancing Technology

The industry continues to seek

engineering and technological solutions to increase its energy and

carbon efficiency. Efforts are underway to engineer better hull and

propeller designs, implement waste heat recovery, and reduce onboard

power usage to minimize emissions. Moreover, the industry is

studying opportunities to switch to lower carbon energy sources such

as Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) and bio fuels.

- Improving Operations

Industry members are implementing

a wide range of operational strategies to reduce energy use. This

includes employing advanced information technology to aid in

operational decision making to improve efficiency, including vessel

routes, speeds, load factors, and other fleet management strategies

that promote conservation.

- Partnering for Progress

Many liner shipping companies

are members of the Clean Cargo Working Group, and adhere to

environmental stewardship guidelines established by Business for

Social Responsibility.14 Members voluntarily track

emissions, set efficiency targets, and examine ways to offset

emissions through certified international programs. In addition to

the wide range of steps the industry is taking on its own accord,

the WSC and its members are working through the International

Maritime Organization to develop uniform standards for improving the

energy efficiency of ship designs and exploring what global legal

structure would best serve to reduce carbon emissions from maritime

shipping.15

|

8 |

Second International Maritime

Organization Green House Gases Study 2009 |

|

9 |

http://www.imsf.info/papers/NewOrleans2009/Wally_Mandryk_LMIU_IMSF09.pdf |

|

10 |

Comparison is based on the CO2 emissions

by transport mode provided by The Network for Transport and the

Environment. |

|

11 |

American Association of Wine Economists,

“ Red, White, and Green: The Cost of Carbon in the Global

Wine Trade, ” AAWE Working Paper #9, Victor Ginsburgh, Oct.

2007. Available at:

http://www.wine-economics.org/workingpapers/AAWE_WP09.pdf |

|

12 |

http://www.ticonferences.com/gds_europe/whitepapers/Nearshoring_Beat_Simon.pdf |

|

13 |

Ship Efficiency Trend Analysis, Report

2008/MCS/ENV/SES/SES08-008, Marine Consultancy Services, Lloyd's

Register, London, October 2008. |

|

14 |

See:

http://www.bsr.org/consulting/working-groups/clean-cargo.cfm |

|

15 |

See

http://www.unctad.org/sections/wcmu/docs/cimem1p09_en.pdf

See: IMO Energy Efficiency Design Index and the Energy Efficiency

Operational Index, and the Shipboard Efficiency Management Plan. |

- Why is the shipping industry participating in the effort

to reduce carbon emissions and address global warming?

-

- To be responsible environmental stewards.

The liner

shipping industry and its customers recognize that environmental

stewardship requires their participation in developing an effective

way to address their carbon dioxide emissions.

- To inform the process.

The process of setting

international carbon management policy must be guided by scientific,

technical, economic and operational knowledge. Policy solutions must

be environmentally effective, realistic, and sustainable. The

resulting carbon regime must be global in scale, legally binding,

and applicable to all ships. It would also be counter productive to

prejudice ocean transportation vis à vis other forms of

transportation that are actually more carbon intensive.

- To ensure an effective international standard is

achieved.

The industry recognizes that an international,

environmentally effective regulatory regime is the best way to avoid

a confusing and inefficient tangle of carbon emission regimes

established by different regional, national or local governments.

- To achieve lower fuel costs through improved

efficiency.

Reducing carbon emissions by improving ships'

energy efficiency will lower fuel consumption while ensuring that

the movement of goods by sea remains the most carbon efficient means

of moving goods from their point of production to the marketplace.

- What is the expected trend in carbon dioxide emissions

from the shipping industry?

-

- Because of its economic and environmental advantages over other

transportation modes, the reliance on ocean shipping to transport

raw materials and manufactured goods internationally is expected to

rise. The U.N.'s International Maritime Organization (IMO) has

estimated that without changes in current operating efficiencies and

with increasing trade volumes, total ship emissions of CO2 will

increase. However, introduction of new technology, changes to ship

and engine design and improvements to operating procedures will

ensure a much slower rate of growth for CO2 emissions. Forecasting

exactly how much CO2 emissions will be attributable to liner

shipping in future years is subject to considerable uncertainty due

in part to variations in international trade volumes, but more

importantly due to continuing improvements in vessel efficiency that

have not yet been quantified, and the effect of expected global CO2

rules to be developed under the IMO.16

-

- What are the potential methods of reducing carbon

emissions from marine shipping?

-

- There are a wide range of efforts underway to increase energy

efficiency in the shipping industry and thereby reduce CO2

emissions. Technical methods include improved ship/hull

design to reduce drag, and more efficient propulsion systems,

including engines that use low carbon fuel. Operational methods

include employing advanced information technology to manage vessel

weight, reducing speed, and improved weather routing to maximize

fuel efficiency.17

-

- What incentives currently exist for the industry to lower

fuel use and carbon emissions?

-

- Fuel costs are a dominant factor in the bottom line

profitability of shipping companies. Fuel costs account for as much

as half of a container ship's operating expenses. Accordingly,

market forces already provide a significant incentive for the

industry to minimize energy use (and therefore emissions). This

incentive will continue to intensify as energy prices resume their

expected upward climb due to market conditions, even in the absence

of new climate change policies that may or may not increase fuel

prices further.18

-

|

16 |

See IMO, “ Prevention of Air

Pollution from Ships, ” MEPC 59, INFO. 10, April 9, 2009.

available at:

http://www.imo.org/includes/blastDataOnly.asp/data_id%3D26047/INF-10.pdf |

|

17 |

See: OECD, Joint Transport Research

Center, Discussion paper No. 2009-11, “ Greenhouse Gas

Emission Reduction Potential from International Shipping, ”

May 2009, at

http://www.internationaltransportforum.org/jtrc/DiscussionPapers/jrtcpapers.html |

|

18 |

See:

http://money.cnn.com/2008/12/17/news/economy/oil_eia_outlook/?postversion=2008121716 |

- III. Air Emission Regulation and the

Shipping Industry

-

- Currently, what is the international process for

regulating greenhouse gas emissions from ocean going vessels and

what are the next steps?

-

- Governments across the globe establish legally binding

international standards through the United Nation's International

Maritime Organization (IMO). The IMO is the appropriate forum to

create a comprehensive legal regime to address vessel carbon

emissions, because ships are mobile assets that are registered in

many different flag states and call at many different ports around

the world. Ships need a predictable and uniform set of regulations.

-

- Effective carbon emission reduction policy also favors an

international regime that applies to ships wherever they may be

operating, because that is the approach that truly reduces CO2 from

the shipping sector world wide. More limited national or regional

schemes would only address emissions associated with certain voyages

or within certain jurisdictions. Development of an effective climate

regime applicable to international shipping should apply to all

international ship movements across the globe.

-

- The IMO also possesses unique technological, operational, and

legal expertise in the ocean shipping sector. Through the

establishment of binding international regulations, the IMO provides

for a consistent and uniform set of standards for ships operating

throughout the world, greatly enhancing predictability, compliance,

enforcement, and the achievement of shared environmental objectives.

-

- In 2008, the IMO successfully created a rigorous, new regulatory

regime for those ship emissions that can adversely affect human

health, namely nitrous oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx) and

particulate matter (PM). Those rules were established as part of

Annex VI to the International Convention for the Prevention of

Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) and are being implemented around the

world. Annex VI, however, did not directly address carbon emissions.

-

- Governments at the IMO are now engaged in negotiations to

develop a global carbon emissions regime applicable to shipping. The

organization is also drafting specific standards concerning ship

design and other technical issues aimed at reducing CO2 emissions.19

Most stakeholders expect the current negotiations to lead to a final

agreement sometime in 2011.

-

- At the same time, governments participating in the United

Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are focused

on developing a successor to the “Kyoto Protocol”, whose

provisions are effective through 2012. The Kyoto Protocol does not

address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with international

aviation or shipping. Instead, GHG emissions associated with

international aviation and marine shipping are expected to be

addressed through negotiations at the International Civil Aviation

Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization

(IMO). Both of these organizations were created to facilitate

international agreement on standards applicable to these sectors,

which routinely operate across numerous national borders and are

subject to unique technology considerations. Nevertheless, some

countries have called for maritime and aviation activities to be

regulated under the UNFCCC, while other governments have strongly

argued that international maritime emissions should be addressed

through the IMO and international aviation emissions should be

addressed through the ICAO. The next round of comprehensive

international talks pursuant to the UNFCCC is scheduled to take

place in Copenhagen in December, 2009.

-

- The outcome of these UNFCCC negotiations should help better

define the overall direction of climate policy. Developments at the

UNFCCC in December will further shape the debate at the IMO as those

negotiations continue in the spring of 2010. The next meeting of the

IMO Marine Environment Protection Committee to address carbon

emissions is scheduled for March 2010.

-

|

19 |

See: IMO Energy Efficiency Design Index

and the Energy Efficiency Operational Index, and the Shipboard

Efficiency Management Plan. |

- What are the issues that make reaching agreement

challenging? Why is implementation difficult if everyone agrees on

the need to reduce CO2 emissions?

-

- CO2 regulatory regimes do not yet exist in most countries. It is

both technically and politically difficult to create such systems

for fixed emission sources (like power plants) in domestic

economies. It is even more challenging to address mobile

transportation sources, like automobiles, rail, aviation and

shipping. The challenge of addressing these mobile sources becomes

even more complex when those sources operate under the registries of

different nations, call at ports in multiple nations, and generate

emissions on the high seas outside any nation's jurisdiction.

-

- The IMO has in fact made substantial progress on developing an

energy efficiency design index for new ships to reduce carbon

emissions. It is generally accepted, however, that such a design

index, if only applied to new ships, is unlikely, by itself, to

sufficiently address the issue. Accordingly, the IMO is considering

several proposals characterized as “market based instruments”

(MBIs) and other hybrid proposals to create a more comprehensive

regime. These proposals are novel, and there is little precedent or

experience to guide governments. While it appears probable that the

IMO will develop a new convention in the foreseeable future, one

should recognize that the issues being considered present unique

challenges. The following provides a short description of some of

those challenges.

-

| |

- Macro Political Questions in the Climate Debate

The

IMO's regulatory regimes are based on the principle that all

ships, regardless of who owns them or where they are registered,

should comply with the same rules. The World Shipping Council and

other industry organizations strongly support this principle.

Furthermore, a carbon emission reduction regime would have little

positive effect on climate change concerns if a ship operator

could avoid it by changing the registration of its ship.-

- At the same time, however, there is a macro political

disagreement between developed and developing nations about

appropriate restrictions on carbon emissions. The United Nations

Framework Climate Change Convention (UNFCCC) and “Kyoto

Protocol” distinguished between Annex I countries with one

set of carbon emission reduction obligations and lesser developed

non Annex I countries that did not have such obligations.20

-

- Additionally, only a little more than one third of the world

cargo fleet is registered in Annex I countries. Many non Annex I

countries under the existing Kyoto Protocols insist that a new

global carbon regime must not impose burdens on their developing

economies. Other governments insist that the carbon emissions

from non Annex I countries now and projected in the foreseeable

future are so substantial that there can be no meaningful impact

on CO2 emissions or their effect on climate without the

participation of these governments and their economies.

-

- This set of political disagreements between governments is

beyond the capacity of the shipping industry to resolve, but

these issues will need to be addressed before the content of a

new regime can be developed.

-

- Market Based Instrument Options

Market based

instruments (MBI) include a variety of economic or market

oriented incentives and disincentives, such as taxes or tax

credits, new fees, or tradable emissions limitations, often

referred to as “Cap and Trade”.-

- Marine Fuel Levy: One MBI concept being given

consideration at the IMO is the establishment of an international

“levy” on marine fuel, with the revenues being

dedicated to a new United Nation's climate fund. Proponents

advocate that the levy approach would be easier to implement and

operate than other MBI approaches being considered. This proposal

has been made by Denmark, and has been set forth in more

detail and with more specifics than other MBI proposals.21

Issues surrounding it include the following:

-

- Will governments be willing to adopt a UN administered

international levy on the sales of fuel?

- What would be the mechanism for collection and

enforcement?

- What entity should be responsible and accountable

for the collection of the revenues associated with the fund? What

is the enforcement scheme to ensure the payment of the levy?

- What

is the role of port states in that enforcement scheme? What are

the penalties and consequences to buyers and/or sellers who try

to evade payment of the fee?

- What would be the level of the levy to be applied? How would

it be set, raised, lowered or suspended?

- Assessing fees to a product will make it more expensive and

will thus cause users to consume less of it, but predicting

precise emission reduction results from a levy is problematic.

For that reason, advocates of the concept argue that carbon

emissions reductions would also be accomplished from this

proposal via the use of the revenues generated from the levy for

carbon mitigation projects. Questions about the control and

management of such a fund are many, including:

- Who would

control the disbursement of the revenues collected?

- Is the

Clean Development Mechanism of the UNFCCC the most appropriate

and efficient vehicle for ensuring the funds are productively

used for CO2 reduction?

- Should the funds, or a portion of the

funds, be devoted to research and development that is specific to

improving fuel economy in the world's shipping fleet, alternative

propulsion systems, and other measures to reduce CO2 emissions -

both in the short term and long term? If yes, what entity would

be responsible for determining which research institutions and

other stakeholders receive the funds and that the work is

completed and disseminated?

- If the funds are to be split

between non maritime CO2 reduction projects and research and

development projects specific to the maritime sector, what should

be the relative split in funding?

- What mechanism should be

used to ensure that projects actually result in CO2 emission

reductions as opposed to theoretical or paper reductions?

- Is the levy a flat, uniform assessment per ton of fuel, or

does the amount of the tax vary depending on the efficiency of

the vessel in order to create an additional economic incentive

for the construction and operation of more efficient vessels?

Japan, for example, has proposed that a vessel operator should

get a rebate under the levy system if it improves vessel

efficiency.22

- This concept has been proposed as an alternative market based

instrument to emission “cap and trade” type concepts.

If this course were pursued, industry would need assurance that

other measures are not also adopted so that it faces both a fuel

levy plus other market based instruments.

- Cap and Trade or Emissions Trading: The

European Commission, some European governments, and some industry

groups have expressed support for the idea of developing an

alternative carbon emissions trading system as the most

appropriate MBI. Unlike the Danish levy proposal, however, there

has been no proposal made that specifically describes how such an

emissions trading system would function at an operational level.

The absence of a clear proposal has made discussion and

assessment of the concept difficult. If this avenue were to be

pursued, a significant number of questions would need to be

addressed, as the design and operation of an emission trading

proposal is likely to be more complicated than a levy on marine

fuels. The unresolved issues include:

-

- How is a “cap” on emissions from shipping

established?

- What is the level of the cap and how much is it

lowered over what period of time?

- What is the baseline year

for establishing the cap?

- Will allowances be allocated in a

manner that gives credit to those vessel operators that have

implemented fuel efficiency efforts to date?

- How are the allocations of the emission allowances within the

cap distributed amongst the various sectors of the industry?

- Are

they auctioned? If so, by whom?

- Are they sold at a fixed

price, and if so, who sets that price?

- If sold or auctioned,

who receives the revenues?

- What are the permissible uses of

the revenues raised? (Additional questions similar to those that

exist for the marine fuel levy proposal discussed above must also

be addressed.)

- Are the emission allowances allocated at no

charge? If so, by whom? According to what criteria?

- Who is covered by the cap? What vessels? Are there vessels

that are not covered?

- Who must hold the emission allowances? The ship owner? The

ship operator?

- What are the trading characteristics of the allowances? For

example:

- Once allocated, are the emission allowances freely

tradable? Are the allowances issued and sold on an annual basis

or a multi year basis?

- Is there a limit on how many allowances

may be purchased or acquired by a particular vessel or

company?

- Is there a restriction on who may purchase

allowances?

- Is there any expiration or “use-by”

date on an emission allowance or can they be “banked”

indefinitely?

- Does an emission allowance shrink in size over

time at the same rate as the total emission cap is reduced over

time?

- May ship operators purchase and use carbon emission

allowances from other industrial sectors?

- Most stakeholders

supporting development of a cap and trade system for maritime

emissions have argued that such a system must be “open”.

An open system would allow trading of allowances across

industrial sectors, but also requires, by definition,

establishment of an economy wide cap and trade system.

- If the

countries that have established such cap and trade systems are

limited to certain developed countries, how does the system

function in the shipping sector, which constantly crosses borders

and operates on a global scale?

- If governments do establish a

cap for the economy as a whole, what criteria must govern the

regimes establishing such allowances in other sectors to be

acceptable for use by the maritime industry under its regime? 23

Who establishes and enforces such criteria?

- Can such an

emission trading system exist in the absence of a comprehensive,

international UN agreement and regime coming out of the

Copenhagen UNFCCC meetings?

- How could the IMO, as a

specialized maritime regulatory entity, monitor and administer a

cross sectorial trading process?

- If the emission trading

system is not an open system allowing for cross sectorial

trading, but instead the cap and trade regime is a closed system

governing only shipping, what would realistic carbon emission

caps be and how would the system allow maritime shipping to

service the expected increase in global commerce over time?

- How is the system enforced? (Similar questions may exist for

the fuel levy proposal.)

- For example, must emission allowances

be surrendered in order to purchase fuel? If so, the similarities

to a levy system are significantly increased, although

enforcement against fraudulent allowances and allowances

generated by non maritime sources may be more difficult than

simply collecting a tax.

- Does one require that all fuel oil

suppliers, whether they are located in a State party to the

Treaty or in a non party State, be registered as proposed in the

global levy system?

- Is a reporting scheme from vessels and/or

fuel suppliers necessary? What would that be?

- Such allowances

would need to be registered and monitored in some manner to

protect against cheating and counterfeiting. How does the

maritime sector administer such a system when allowances are

generated from a multitude of sectors and countries where many of

the countries are not party to or otherwise part of the system?

What is the responsibility of the flag state with respect to

enforcement?

- How would an arriving ship to a given port state

demonstrate compliance?

- What are the consequences of non

compliance?

- If a ship or ship operator does not possess enough allowances

to cover its emissions, what happens? Does it pay a tax or

penalty in order to continue to operate? If so, how is the level

of the penalty established? If not, must it cease operation until

it obtains sufficient emission allowances?

- Do all transportation modes have a similar carbon regime

applied to them so that maritime commerce is not disadvantaged

vis à vis other transport modes?

- Hybrid Proposals: Other governments at the IMO

have made hybrid MBI proposals that offer a variation on the

Danish levy concept or that are different from either the marine

fuel levy or emission trading systems. More such proposals are

likely to emanate from governments after the UNFCCC Copenhagen

meeting in December 2009 and prior to the next IMO Marine

Environment Protection Committee meeting in March of 2010.

-

- As previously mentioned, Japan has proposed that the

Danish levy concept be modified to provide a rebate of the levy

if a vessel operator improves the efficiency of its vessel. 24

Some have noted with favor that this idea seeks to incentivize

improved vessel efficiency and thus reduced carbon emissions.

Some have noted with disfavor that this idea would provide a

greater reward to an operator of an existing, inefficient vessel

for marginal improvement than a new, more efficient vessel that

has built improved efficiency into it.

-

- Additionally, the United States has proposed that all

vessels, both existing and new builds, be subjected to the new

energy efficiency design index. In essence, this proposal would

establish mandatory efficiency standards for all ships (new and

existing) that increase in stringency over time. This system

would also facilitate trading of efficiency credits so that ships

that operate below the standards may trade credits with less

efficient ships in the existing fleet. This would constitute a

type of “cap and trade” of ship energy efficiency

rather than a cap and trade of carbon emissions.25 If

a ship fell below the energy efficiency standards, it would need

to purchase energy efficiency credits from other ship operators

that perform above the standards or otherwise face punitive

measures. Some stakeholders have noted favorably that such a

system would effectively require the world's vessel fleet to

significantly improve its energy efficiency, thereby reducing

emissions yet avoid the political and practical complications

associated with both an emissions cap and trade system and an

international levy on marine fuels. Others have noted that the

proposal does not yet provide sufficient detail, particularly

with respect to existing ships that fall below the required

efficiency standard and cannot find design index credits to

purchase from those who operate more efficient ships.

|

|

20 |

http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php |

|

21 |

Submittal by Denmark to the 59 th Session

of the International Maritime Organization's Marine Environment

Committee, MEPC 59/4/5, April 2009 |

|

22 |

Japanese submittal to the 59 th Session

of IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee, MEPC 59/4/34,

Consideration of a Market-Based Mechanism to Improve the Energy

Efficiency of Ships Based on the International GHG Fund] |

|

23 |

For example: Assume a particular country

gives landholders emission allowances for not developing forested

property. Can a vessel operator purchase those allowances for use

in a maritime emission trading system? If after purchased by the

vessel operator the landowner develops the property, what happens

to the vessel operator's emission allowances? For example, could a

vessel that needs emission allowances to operate a service between

Morocco and Germany, purchase and use allowances issued in China? |

|

24 |

Japanese submittal to the 59 th Session

of IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee, MEPC 59/4/34,

Consideration of a Market-Based Mechanism to Improve the Energy

Efficiency of Ships Based on the International GHG Fund] |

|

25 |

Submittal by the United States of America

to the 59 th Session of IMO's Marine Environment Protection

Committee, MEPC 59/4/48, Comments on MEPC 59/4/2 and an Additional

Approach to Addressing Maritime GHG Emissions.] |

- What challenges does the unique and complex nature of the

shipping industry pose in crafting effective and responsible climate

policy?

-

- Global complexity.

The global nature of ocean shipping

poses a challenge for the effort to craft coherent and practicable

carbon emissions policy. The international fleet is owned,

registered, and operated in many different parts of the world. The

industry's mobile, trans boundary operations pose a much more

complex range of political, practical, and administrative

difficulties than economic sectors characterized by fixed operations

and stationary sources of greenhouse gases. Significant challenges

include how to properly account for international emissions, how to

enforce rules equitably among diverse jurisdictions, and how to

maintain competitive fairness and balance in an inherently global

business.26

- Duplicative Jurisdiction

While complex and

challenging, an international IMO regime would avoid many of the

problems that would arise if various nations, regional blocs, and

localities were to try to impose their own carbon emission rules,

regulations, and regimes. The potential for a multi jurisdictional

patchwork of rules would raise significant concerns about regulatory

duplication, inefficiency, and incompatibility. Ocean shipping is a

global enterprise with operations that span many different

geographic, national, and regulatory jurisdictions. Some container

ships call on 20 different ports in 8 different countries per year.

- Integrated Supply Chain

Another critical factor that

must be considered is that maritime shipping is part of a large,

complex, and inter connected global supply chain. Changes in

shipping services can produce effects up and down the chain with

significant economic and environmental consequences. For example,

carbon rules that raise the cost or limit the availability of

certain traded goods may cause consumers to buy alternative products

with a greater carbon footprint, in part from increased dependence

on carbon intensive ground transportation. Moreover, irregular or

reduced liner services may affect the inventory management practices

of producers raising demand for carbon intensive infrastructure and

services such as storage, utilities, and ground transportation. A

recent study found that the carbon footprint of the seaborne

importation of wine to the eastern U.S. is significantly less than

the emissions from transporting domestic product by ground, rail, or

air. In this instance, economic or regulatory restrictions on ocean

shipping could have adverse, unintended consequences resulting in

higher net carbon emissions.27

- Long Lead time Requirements

The high cost and long

life of cargo ships present challenges that must be factored into

climate solutions. A single container ship capable of carrying 8,500

TEU's costs approximately $100 million and must be ordered three or

more years in advance of delivery. It will operate for 20 to 25

years. Additionally, ships are often ordered in a set of four to

ten, since multiple ships of a similar size are needed to operate a

single liner service. For these reasons, changes in design

specifications require ample planning and sufficient lead time to be

smoothly implemented.28

|

26 |

To illustrate, consider the example of a

liner shipping service comprised of nine liner shipping vessels,

registered in four different nations, operating in a four carrier

Vessel Sharing Agreement, that provides regular weekly service

between ports in four different Asian nations and four different

European nations, with an intermediate port call in North Africa,

and therefore providing 20 different cargo port pair combinations. |

|

27 |

American Association of Wine Economists,

“ Red, White, and Green: The Cost of Carbon in the Global

Wine Trade, ” AAWE Working Paper #9, Victor Ginsburgh, Oct.

2007, available at

http://www.wine-economics.org/workingpapers/AAWE_WP09.pdf |

|

28 |

Daniel Machalaba and Bruce Stanley, Wall

Street Journal published by Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. See:

http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/06283/728846-28.stm |

What do these complexities and challenges mean for the

likelihood of a carbon emission regime applicable to shipping?-

- The objective of an environmentally effective agreement to

reduce carbon emissions from shipping and the industry's objective

of a single, predictable international regulatory regime are highly

compatible. Indeed, improved energy efficiency, reduced fuel

consumption, and fewer emissions are outcomes that should be

strongly supported by all the relevant stakeholders. Many of the

stakeholders, including the World Shipping Council and its member

companies, are optimistic that a global solution is feasible in the

2011 timeframe. It is too early to predict the precise nature of

that regime, as governments and nongovernmental organizations are

still in the formative process of developing proposals. The pace of

such developments is expected to accelerate in 2010 after the

Copenhagen UNFCCC discussions have concluded.

-

- The World Shipping Council and its member companies strive to

improve the climate performance of shipping and will continue to

strongly support the creation of an effective and practical IMO

regime to address these issues. Even in the absence of a new

international regime, these companies will continue to pursue

reduced carbon emissions through changes in ship design, fuel

consumption and ship operations.

-

- IV. Summary

-

- Developing an effective international regulatory regime to

reduce carbon emissions from shipping requires governments and

industry to address a host of complicated political and technical

questions. There is limited precedent to build upon. There is no

viable CO2 emission regulatory system (other than engine or mileage

standards) functioning anywhere in the world that is applicable to

mobile transportation sources, whether that be automobiles (which

emit more CO2 than ships29), trucks, trains, planes,

tugboats, ferries, and other mobile sources. Most nations have not

established such regimes for their own domestic economies. There is

no functioning regime in place for other transnational industries,

such as international aviation.

-

- The IMO is the most appropriate forum to develop this regime for

shipping, and the success of the IMO in developing the MARPOL Annex

VI regulatory regime for NOx, SOx and particulate matter (PM)

emissions from ships demonstrates that it is an environmentally and

globally effective regulatory body. The World Shipping Council and

its member companies are actively engaged in efforts at the IMO to

develop an effective global agreement. While the challenges to

negotiating a global agreement are significant, the World Shipping

Council and numerous other organizations are strongly committed to

helping forge agreement of an effective global regime. More specific

proposals from participating governments and organizations on both

the political and technical aspects of this effort are expected, and

many observers are hopeful that significant progress can be made

following the UNFCCC climate negotiations scheduled for December

2009 in Copenhagen.

-

|

29 |

International Council on Clean Transport

from data supplied by the International Energy Agency, 2008. |

- In the interim, governments at the IMO have agreed to key

principles that must apply to the new regulatory regime for carbon

emissions from ships. They require that regulations:

-

- Effectively reduce CO2 emissions.

- Be binding and include all flag states.

- Be cost effective.

- Not distort competition.

- Be based on sustainable development without restricting trade

and growth.

- Be goal based and not prescribe particular methods.

- Stimulate technical research and development in the entire

maritime sector.

- Take into account new technology.

- Be practical, transparent, free of fraud and easy to administer.

- The World Shipping Council and its member companies endorse

these principles and will work with governments at the IMO to ensure

that these principles are appropriately addressed in new regulations

for carbon emissions from ships.

-

- For additional information about the liner shipping industry,

please contact the World Shipping Council.

-

|

In Washington, D.C.

1156 15 th

Street N.W.

Suite 300

Washington, D. C. 20005

U.S.A.

+1

202 589 1230 |

|

In Brussels

Avenue des Gaulois

34

B 1040

Brussels

Belgium

+32 2 734 2267 |

|

Email the Council at: |

info@worldshipping.org |

|

|

Visit the Council's website at: |

www.worldshipping.org |

|

|